India’s majestic mountains and lush valleys are home to some of the world’s most breathtaking retreats. The hill stations in India offer a perfect escape from the scorching heat and bustling city life, providing cool climates, stunning landscapes, and serene environments.

From the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas to the misty mountains of the Western Ghats, India hill stations cater to every type of traveler—whether you seek adventure, romance, or peaceful solitude.

This guide explores the top hill stations in India, showcasing destinations that have captivated travelers for generations with their natural beauty, colonial charm, and unique cultural experiences.

Shimla: The Original, Now Overcrowded

Shimla launched India’s hill station concept as the British Raj’s summer capital. That history saturates the town—the Mall Road’s Victorian architecture, Christ Church’s Gothic spire, the Viceregal Lodge where decisions affecting millions were made over afternoon tea.

The problem is simple: too many people discovered what worked about Shimla. Peak season weekends see the town overrun by tourists from Delhi and Punjab, creating traffic jams at 2,200 meters that defeat the entire purpose of mountain escape. The Mall Road becomes a slow-moving human river. Hotels charge premium prices for ordinary rooms.

Visit during weekdays in shoulder seasons (March, September-October) and Shimla’s appeal resurfaces. The colonial architecture remains impressive. The ridge walks offer genuine Himalayan views. The nearby forests still shelter leopards and barking deer. The toy train from Kalka delivers scenic satisfaction.

What works: Accessible from Delhi (345 km), genuine historical significance, established infrastructure, proximity to better destinations like Narkanda and Chail.

What doesn’t: Weekend crowds, overdevelopment, inflated prices, loss of the peace that originally justified hill stations.

Best for: First-time visitors wanting accessible Himalayan introduction, history enthusiasts, those using it as a base for exploring Himachal’s quieter corners.

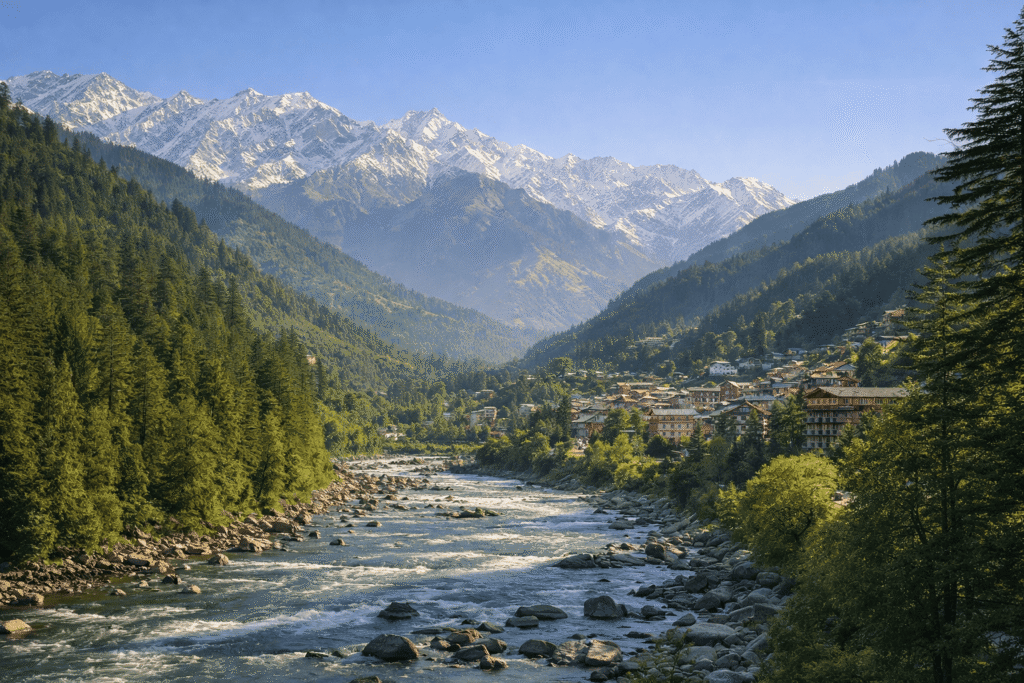

Manali: Adventure Capital That Lost Its Soul

Manali split into two incompatible versions. Old Manali retains some backpacker charm—cafes, guesthouses, and a laid-back atmosphere where long-term travelers decompress. The main town became a concrete sprawl of hotels, restaurants, and shops selling the same jackets and souvenirs in endless repetition.

But Manali’s setting still delivers. The Beas River valley, the deodar forests, the snow peaks visible from town—the natural assets that attracted visitors initially haven’t disappeared under the development. And Manali’s position as an adventure hub remains unmatched: trekking, rafting, paragliding, skiing (winter only), mountain biking.

The town works best as a base for experiences elsewhere. Spend your days in Solang Valley paragliding, trekking to Bhrigu Lake, or driving over Rohtang Pass. Return to Manali to sleep, eat, and organize the next day’s activities. Trying to find peaceful mountain contemplation in the main bazaar leads only to disappointment.

What works: Unmatched adventure activity access, stunning surroundings, Old Manali’s remaining charm, excellent connectivity.

What doesn’t: Overdevelopment, traffic congestion, commercialization, loss of the village character it once had.

Best for: Adventure seekers, trekkers using it as a base, those who prioritize activities over atmosphere.

Dharamshala/McLeod Ganj: Where Tibet Lives in Exile

McLeod Ganj technically sits above Dharamshala, but most visitors focus entirely on the upper town where the Tibetan government-in-exile created something unique: a Himalayan hill station infused with Buddhist culture, Tibetan refugees, and international seekers drawn to both.

The Dalai Lama’s presence (when he’s in residence) adds gravity. The Tsuglagkhang Complex, Namgyal Monastery, and Tibetan institutions provide genuine cultural engagement beyond typical tourist circuits. Prayer flags flutter everywhere. Monks in burgundy robes walk streets lined with momos shops and Tibetan handicraft stores.

But McLeod Ganj also absorbed typical hill station problems—crowding during peak season, aggressive touts, restaurants serving bland international food to tourists who came seeking authenticity. The balance between living Tibetan community and tourist infrastructure creates constant tension.

The surrounding landscape rewards exploration. Triund trek (9 km, challenging day hike) offers panoramic views. Bhagsu village and waterfall provide easier walks. The Kangra Valley spreads below with tea estates and ancient temples.

What works: Genuine cultural significance, living Buddhist traditions, excellent trekking access, diverse food scene, international atmosphere without feeling artificial.

What doesn’t: Crowding in peak season, some commercialization of Tibetan culture, limited luxury accommodation options.

Best for: Those interested in Tibetan Buddhism, culture-focused travelers, trekkers, people seeking community atmosphere over pure nature isolation.

Mussoorie: Queen of Hills Showing Her Age

Mussoorie’s “Queen of Hills” title dates to British times when it rivaled Shimla as a preferred retreat. The town retains Victorian-era charm in pockets—Landour’s quiet lanes, colonial-era schools, the library bazaar—but much of Mussoorie succumbed to unplanned development.

The Mall Road and Gun Hill area pack dense with tourists, especially weekenders from Delhi (290 km away). But walk 30 minutes from the crowds and different Mussoorie emerges. Landour, the cantonment area, maintains peace with forest walks, old churches, and fewer tourists. The Camel’s Back Road offers a 3-km walking/horseback trail with valley views. The nearby Company Garden and Kempty Falls serve as adequate family outings.

Mussoorie’s advantage lies in accessibility and infrastructure—numerous hotels at all price points, good restaurants, easy transport connections. The disadvantage is that everyone else knows this too.

What works: Accessibility from Delhi, established infrastructure, some genuine colonial atmosphere in Landour, decent food options.

What doesn’t: Overcrowding, loss of character in main tourist areas, commercialization, traffic problems.

Best for: Families wanting easy accessibility, those seeking short breaks from Delhi, visitors comfortable with established tourist infrastructure.

Nainital: Lake Town That Actually Works

Nainital built itself around a natural lake—Naini Lake, 1.4 km long and 470 meters wide, sitting at 1,938 meters altitude. That lake remains the town’s center and saving grace. Morning boat rides on still water, watching mist rise off the surface, walking the Mall Road that circles the shore—the lake provides focus that makes Nainital’s tourism density more tolerable.

The town sprawls up hillsides in layers. The Mall Road and lake area concentrate crowds and commerce. Climbing higher reaches quieter residential areas and forested slopes. The ropeway to Snow View Point (₹300 return) offers panoramic views across Himalayan peaks, weather permitting.

Nearby attractions include Naina Peak (2,615 meters, highest point with sunrise views), Tiffin Top (pleasant 4-km trek from town), and several smaller lakes scattered within 20 km. The surrounding Kumaon region rewards exploration—Bhimtal, Sattal, and Naukuchiatal offer quieter lake experiences without Nainital’s tourist intensity.

What works: The lake creates genuine focal point, good tourism infrastructure, proximity to multiple other lakes, accessibility from Delhi (320 km).

What doesn’t: Crowding during peak season, commercialization around Mall Road, traffic congestion on narrow roads.

Best for: Lake enthusiasts, families, those wanting established infrastructure with natural beauty, visitors exploring broader Kumaon region.

Darjeeling: Tea, Trains, and Kanchenjunga

Darjeeling operates on a different scale than most Indian hill stations. The town cascades down a ridge at 2,042 meters with views (on clear days) of Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest peak. Tea plantations carpet surrounding hillsides. The UNESCO-listed toy train chugs through impossible gradients. Tibetan Buddhist monasteries add cultural depth.

But Darjeeling struggles with overtourism and infrastructure strain. The town’s steep streets congest with vehicles. Budget hotels proliferate. During peak season (March-May, September-November), the crowds diminish the experience significantly.

What makes Darjeeling worthwhile: the sunrise view from Tiger Hill over Kanchenjunga (when weather cooperates), the tea estate tours showing production from leaf to cup, the toy train ride to Ghoom (even abbreviated versions capture the engineering marvel), the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute honoring the region’s climbing history, and the Tibetan Refugee Self-Help Center preserving craft traditions.

The surrounding region offers alternatives. Kalimpong (50 km) provides similar Himalayan views with fewer tourists. Mirik (49 km) centers on a peaceful lake. The Singalila Ridge trek delivers high-altitude trekking without requiring extreme logistics.

What works: Spectacular mountain views, legitimate tea culture, toy train experience, cultural diversity (Nepali, Tibetan, Bengali influences), excellent regional food.

What doesn’t: Overtourism, infrastructure strain, crowds diminishing the peaceful hill station atmosphere, political tensions occasionally disrupting travel.

Best for: Tea enthusiasts, mountain view seekers, those interested in mountaineering history, travelers who can visit during off-season or use it as a base for surrounding exploration.

Coorg: Coffee Country in the Western Ghats

Coorg (Kodagu) spreads across Karnataka’s Western Ghats as a district rather than a single town, making it functionally different from typical hill stations. Coffee plantations dominate the landscape at 900-1,750 meters altitude. Waterfalls appear after monsoons. Forests shelter elephants and diverse birdlife. Kodava culture—distinct from mainstream Karnataka—adds ethnic character.

Madikeri serves as the district headquarters and main base. Abbey Falls, Raja’s Seat viewpoint, and Omkareshwara Temple provide standard tourist circuits. But Coorg rewards venturing beyond Madikeri: Talakaveri (Kaveri River’s source), Bhagamandala (where three rivers meet), and Nagarhole National Park for wildlife safaris.

The plantation homestay culture makes Coorg special. Family-run estates offer accommodation, home-cooked Kodava food, and insight into coffee cultivation. Walking through coffee plants under shade trees, learning about processing methods, trying freshly roasted coffee—these experiences justify Coorg’s popularity.

What works: Coffee plantation experiences, excellent homestay culture, good food (Pandi curry is mandatory), less commercialized than northern hill stations, accessibility from Bangalore (260 km) and Mangalore (135 km).

What doesn’t: Limited budget accommodation outside homestays, monsoon (June-September) brings heavy rain curtailing outdoor activities, some areas getting overdeveloped.

Best for: Coffee lovers, food enthusiasts, those seeking homestay experiences, visitors wanting Western Ghats environment over Himalayan landscape.

Munnar: Tea Hills That Photographed Themselves to Fame

Munnar’s tea plantations created Instagram’s dream landscape before Instagram existed—rolling hills covered in manicured tea bushes, morning mist, roads snaking through green curves. The scenery at 1,600 meters in Kerala’s Western Ghats looks almost too perfect, like someone optimized reality for photography.

Tourism responded predictably. Munnar became Kerala’s most visited hill station, infrastructure boomed, and peak season (December-January, April-May) brings crowds that compromise the peaceful atmosphere people came seeking.

But the tea plantations remain objectively beautiful. The Tata Tea Museum offers genuine insight into production history. Eravikulam National Park protects endangered Nilgiri Tahr and blooms with Neelakurinji flowers every twelve years (next: 2030). Anamudi Peak (2,695 meters, South India’s highest) challenges trekkers. Mattupetty Dam and Kundala Lake provide pleasant if unessential outings.

Visit during monsoon (June-September) for dramatically green landscapes and far fewer tourists, accepting that mist may obscure views and some activities get curtailed.

What works: Objectively stunning tea plantation landscapes, decent tourism infrastructure, good hotels at various price points, relatively cool weather year-round.

What doesn’t: Heavy tourist traffic, overcrowding in peak season, commercialization in town areas, loss of the isolation that once characterized it.

Best for: Photography enthusiasts, tea lovers, those comfortable with established tourist infrastructure, visitors exploring broader Kerala itineraries.

Ooty: The Original Southern Hill Station

Ooty (Ootacamund) claims “Queen of Hill Stations” status in South India, though that crown feels tarnished by decades of tourism pressure. The British established Ooty in 1821 as Madras Presidency’s summer headquarters, creating the template for southern hill stations.

What remains worthwhile: the Nilgiri Mountain Railway (UNESCO World Heritage toy train from Mettupalayam, 46 km), the Botanical Gardens’ diverse plant collections, and the surrounding Nilgiri landscapes—rolling grasslands, shola forests, and tea estates. Ooty Lake offers boating amid planted eucalyptus. Dodabetta Peak (2,637 meters) provides panoramic views when weather cooperates.

But Ooty suffers from its success. The town itself sprawls with concrete development. Traffic congestion plagues main areas. Peak season crowds (April-June) make the experience actively unpleasant. Budget hotels proliferate with variable quality.

Better alternatives exist nearby. Coonoor (19 km) offers similar colonial atmosphere with fewer crowds. Kotagiri (31 km) remains even less developed. Using Ooty as a brief stop while exploring the broader Nilgiris makes more sense than making it a primary destination.

What works: Toy train experience, established infrastructure, accessibility from Bangalore (270 km) and Coimbatore (86 km), base for exploring Nilgiris.

What doesn’t: Overdevelopment, crowds, commercialization, loss of charm that originally attracted visitors.

Best for: Toy train enthusiasts, those using it as a Nilgiris base, visitors with limited time wanting accessible southern hill station experience.

Shillong: Scotland of the East (Kind Of)

Shillong earned the “Scotland of the East” nickname from homesick British officers who apparently had never actually seen Scotland. But the name stuck, and Shillong at 1,496 meters in Meghalaya’s Khasi Hills offers something distinct from western and northern hill stations.

The town itself sprawls modern and bustling—a proper city rather than a resort destination. But the surrounding landscape delivers: waterfalls (Elephant Falls, Nohkalikai Falls), living root bridges (Cherrapunji area), caves (Mawsmai Cave), and clean villages like Mawlynnong.

Shillong’s appeal lies in its position as a base for exploring Meghalaya—one of India’s most beautiful and least-visited states. The monsoon arrives with intensity here (Cherrapunji holds rainfall records), turning everything impossibly green from June to September.

The local Khasi culture, Christian missionary legacy, and increasing cafe culture create an atmosphere different from Hindu-dominated hill stations. The music scene thrives—Shillong produces nationally recognized rock bands.

What works: Gateway to Meghalaya’s natural beauty, distinct culture, living root bridges nearby, excellent food scene, different vibe from typical hill stations.

What doesn’t: The city itself isn’t particularly charming, infrastructure can be basic, remote location requires committed travel, heavy monsoon rain (pro or con depending on perspective).

Best for: Explorers wanting offbeat destinations, waterfall enthusiasts, those interested in Northeast India’s distinct culture, adventurous travelers comfortable with basic infrastructure.

Auli: Skiing Destination That Works Beyond Winter

Auli sits at 2,500-3,050 meters in Uttarakhand’s Garhwal Himalayas as India’s premier skiing destination. Winter (December-February) brings snow and functional skiing—nothing approaching European Alps standards, but legitimate runs with equipment rentals and instructors.

But Auli works year-round. Summer and autumn reveal meadows, wildflowers, and spectacular views of Nanda Devi and surrounding peaks. The cable car (4 km, Asia’s longest) offers panoramic mountain vistas regardless of season. Trekking routes connect to Valley of Flowers and other Garhwal destinations.

The limited accommodation (mostly GMVN properties and a few private hotels) prevents the overdevelopment that plagued other hill stations. This keeps Auli relatively uncrowded but limits options for visitors.

What works: Genuine skiing in winter, spectacular Himalayan views year-round, less commercialized, cable car experience, trekking access.

What doesn’t: Limited accommodation and food options, accessibility requires effort (Joshimath is 16 km away, then cable car or road), skiing infrastructure basic compared to international destinations.

Best for: Skiing enthusiasts accepting Indian standards, mountain view seekers, trekkers exploring Garhwal, those wanting genuine isolation.

Kasol: Hippie Valley That Commercialized

Kasol in Himachal’s Parvati Valley started as a backpacker secret—a quiet village with mountain views where travelers extended stays turned into months. Israeli tourists discovered it, creating a unique subculture of cafes, trance music, and cannabis tourism.

Today’s Kasol balances that counterculture legacy with mainstream tourism. The village sprawls with guesthouses, restaurants serving Israeli food alongside Indian standards, and shops selling hippie-branded merchandise. But it remains genuinely beautiful—the Parvati River’s turquoise water, the pine forests, the peaks rising to 6,000 meters.

Kasol works better as a base than a destination. Kheerganga trek (12 km), Tosh village (4 km), Malana’s ancient village culture (accessible but sensitive), and various other trails reward those who venture beyond the main street’s cafe scene.

What works: Stunning natural setting, diverse international atmosphere, trekking access, good food options, relatively relaxed vibe.

What doesn’t: Commercialization diminishing original charm, drug tourism attracting police attention, overcrowding in peak season, losing authentic character.

Best for: Trekkers using it as a base, younger travelers comfortable with party atmosphere, those seeking international backpacker culture in Himalayan setting.

Choosing Your Hill Station: Matching Expectations to Reality

The “best” hill station depends entirely on your priorities:

For accessibility and infrastructure: Shimla, Mussoorie, Nainital, Ooty—well-connected, numerous hotels and restaurants, easy family travel.

For cultural immersion: Dharamshala/McLeod Ganj (Tibetan), Coorg (Kodava), Shillong (Khasi), Darjeeling (mixed Nepali-Tibetan-Bengali).

For adventure activities: Manali (rafting, trekking, paragliding), Auli (skiing), Kasol (trekking base).

For relative solitude: Coorg homestays, Auli, Shillong’s surrounding villages, Nainital’s nearby lakes.

For mountain views: Darjeeling (Kanchenjunga), Auli (Nanda Devi), Dharamshala (Dhauladhar range).

For tea/coffee culture: Darjeeling and Munnar (tea), Coorg (coffee).

Common mistakes: Visiting during peak season expecting solitude, staying only in main tourist areas without exploring surroundings, judging entire regions by overcrowded towns, expecting European Alps standards at Indian prices.

Seasonal strategy: Shoulder seasons (March, September-October) offer the best compromise of weather and crowds across most hill stations. Winter (December-February) works for snow enthusiasts and those avoiding crowds. Monsoon (June-September) empties many places and creates dramatic green landscapes, but curtails activities and brings landslide risks.

Conclusion

From Shimla’s colonial elegance to Munnar’s tea-covered slopes, the top hill stations in India offer diverse experiences that create lasting memories.

Each of the hill stations in India featured in this guide brings its own distinct character—whether it’s the adventure opportunities in Manali, the spiritual serenity of Dharamshala, or the romantic ambiance of Darjeeling.

India hill stations are more than just cool-weather retreats; they’re gateways to stunning natural beauty, rich cultural heritage, and unforgettable experiences.

Whichever mountain destination you choose, these hill stations promise the perfect escape to rejuvenate your mind, body, and soul.

Frequently Asked Questions

Manali in Himachal Pradesh is often considered India’s most beautiful hill station, known for its snow-capped peaks, lush valleys, and adventure opportunities. Shimla, Darjeeling, and Munnar are also top contenders for this title.

The three most famous hill stations are:

1-Shimla (Himachal Pradesh) – The “Queen of Hills”

2-Darjeeling (West Bengal) – Famous for tea gardens

3-Ooty (Tamil Nadu) – The “Queen of Nilgiris”

1-Shimla (Himachal Pradesh)

2-Manali (Himachal Pradesh)

3-Darjeeling (West Bengal)

4-Ooty (Tamil Nadu)

5-Munnar (Kerala)

1-Shimla (Himachal Pradesh)

2-Manali (Himachal Pradesh

3-Nainital (Uttarakhand)

4-Mussoorie (Uttarakhand)

5-Dharamshala (Himachal Pradesh)

6-Dalhousie (Himachal Pradesh)

7-Kasauli (Himachal Pradesh)

8-Rishikesh (Uttarakhand)

9-Auli (Uttarakhand)

10-McLeod Ganj (Himachal Pradesh)